Articles | April 5, 2021 | 4 min read

Explaining the Turbulence Around Addressability

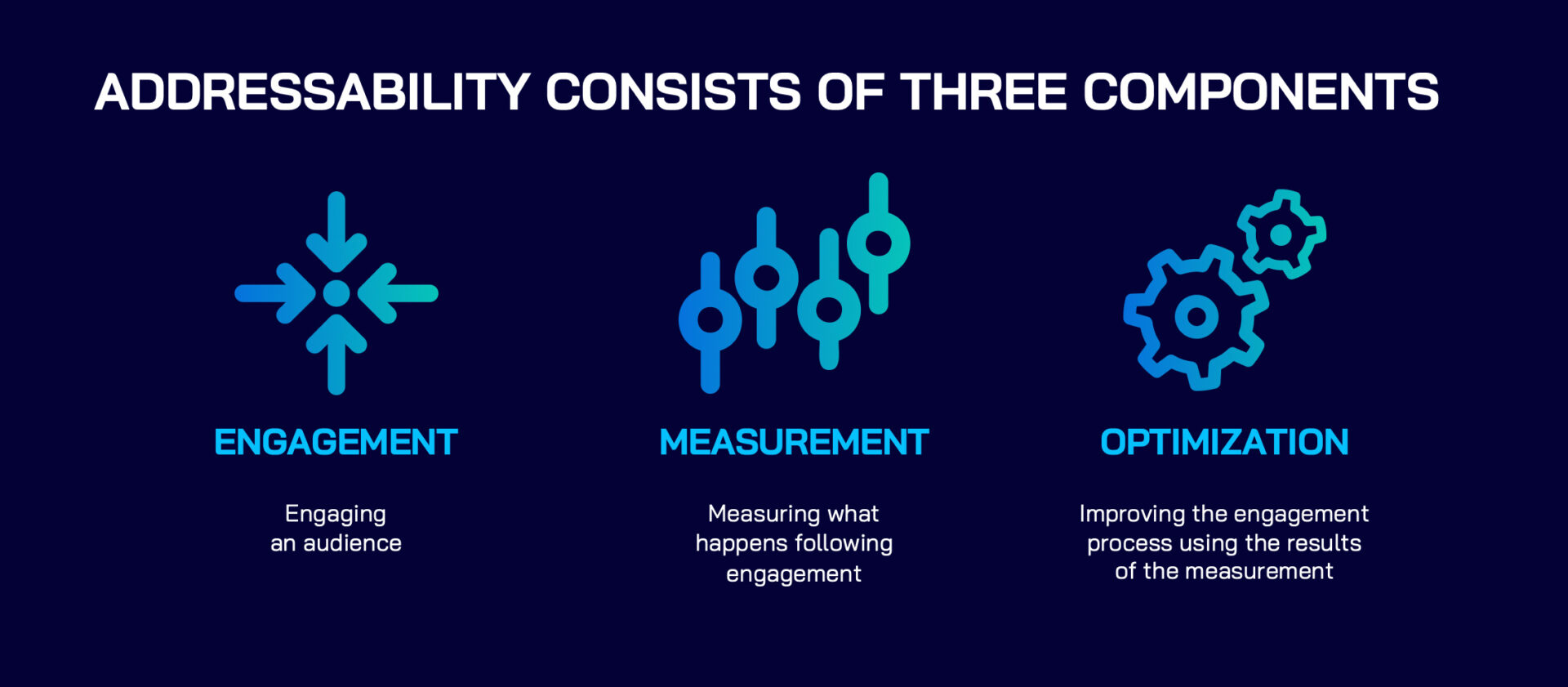

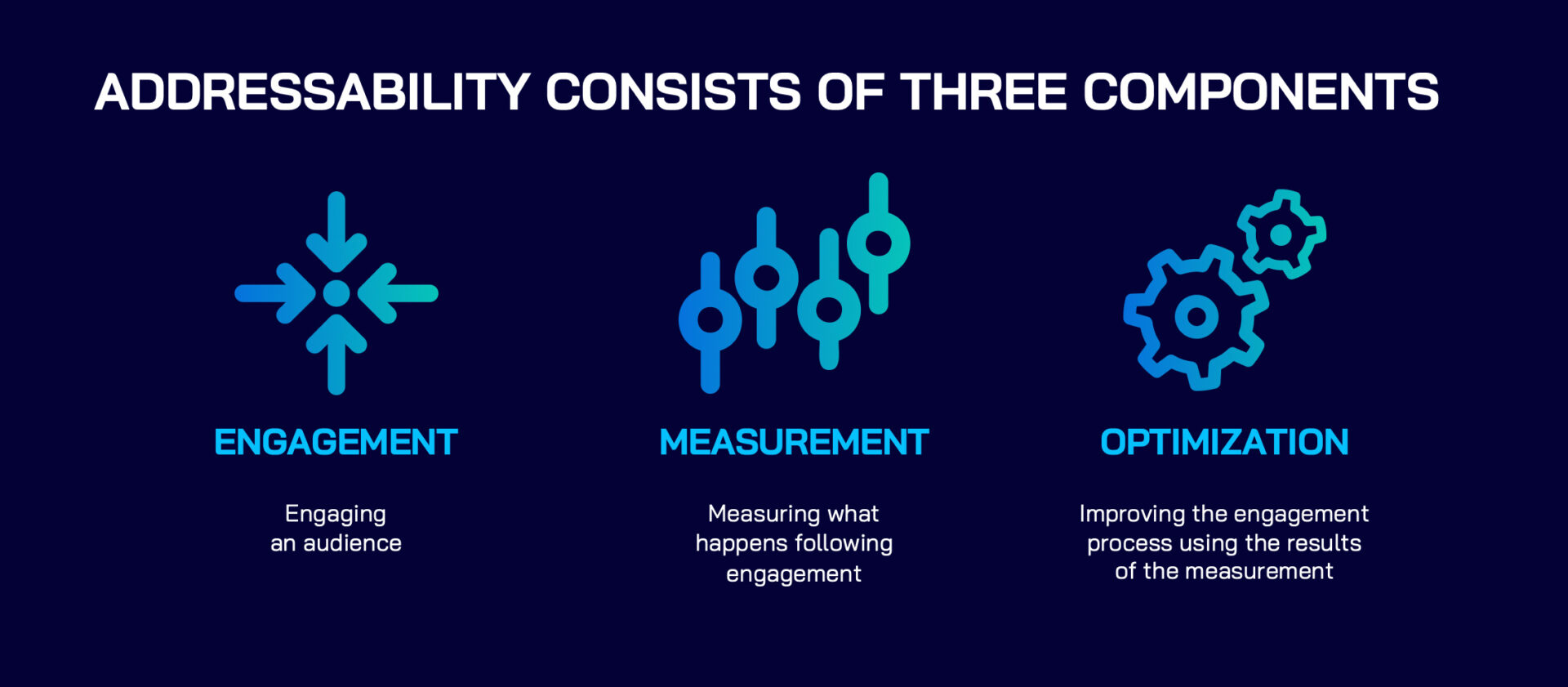

Addressability consists of three components:

To power all three of these critical functions, marketers require a consistent cross-site identifier.

Think of the identifier as the address on the outside of an envelope:

Just as the address enables the mailman to deliver an envelope to the right house, the identifier allows marketers to deliver content to a given browser (or any other web-enabled application).

Thus this identifier (or “ID”) helps the marketer deliver their message to the right audience.

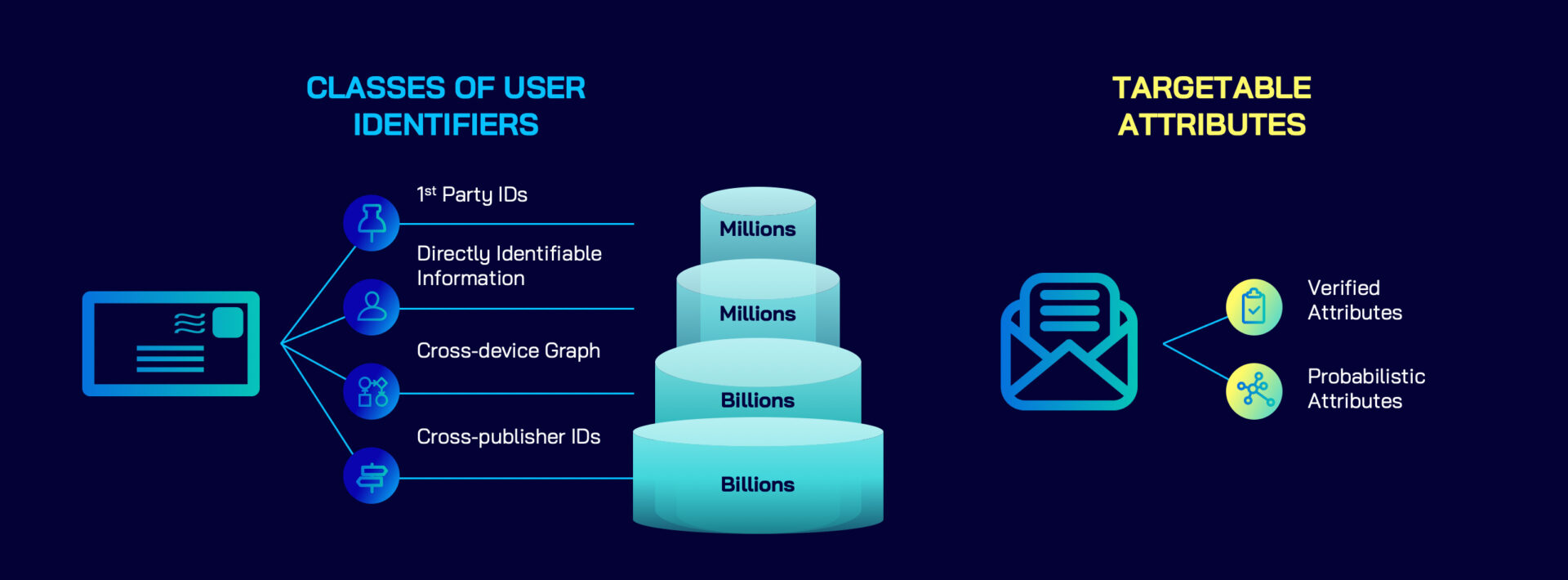

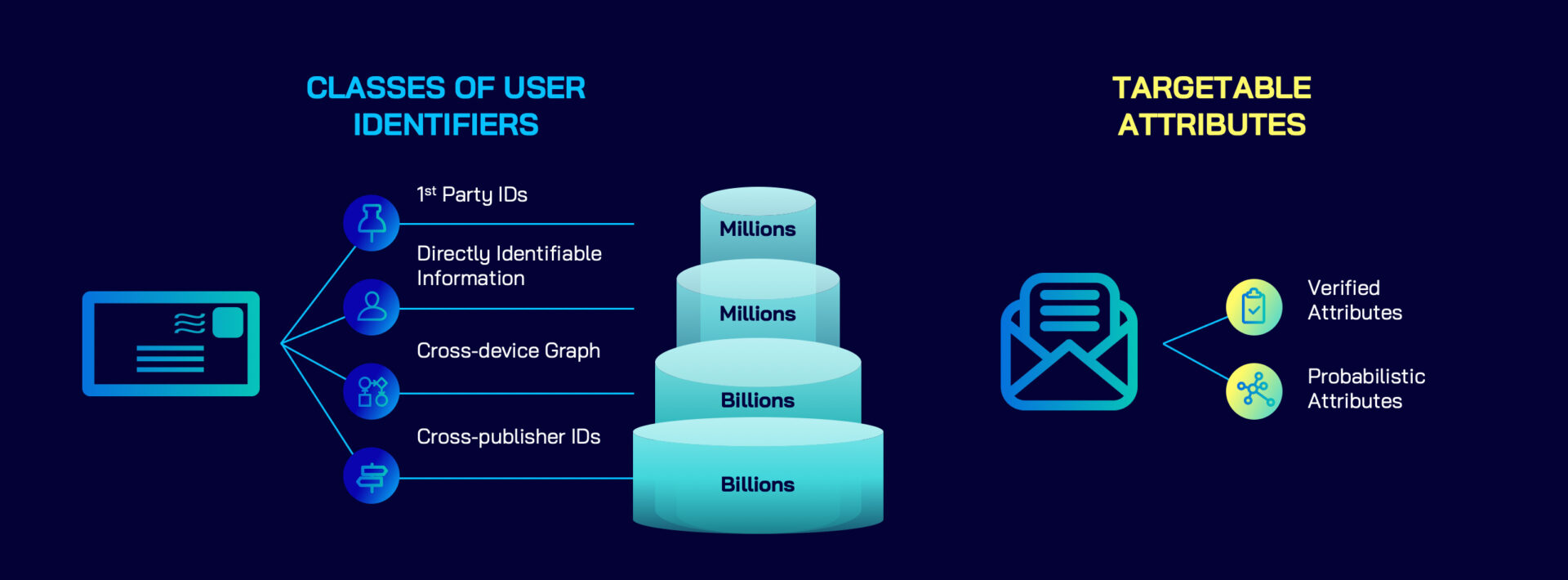

Identifiers differ not just in which application or device they’re associated with. They also differ in whether they’re directly associated with a person (a.k.a, personally identifiable information) or a web-enabled device (a.k.a., pseudonymous identifiers).

The main distinction between these two is whether there’s a way to keep a real-world identity hidden from the organization using the identifier.

Marketers use pseudonymous identifiers for most advertising, so they don’t know the real-life identity of their audience.

This is a critical distinction:

A marketer using a pseudonymous ID might know that a nameless, faceless consumer is visiting ESPN.com. But they don’t know this consumer is named John Q. Smith, aged 47 years, living at 789 Main Street. Returning to the previous analogy, the identifier is the label on the envelope. It is how a marketer’s message (e.g., “Buy this product!”) reaches a given consumer. It is not the why.

The why is explained by the “letter” inside the envelope. The letter contains the consumer’s demographics, interests, buying history, search history, and more.

This inside-the-envelope information is what powers segmentation and audience construction. It explains why a marketer wants to engage one consumer more than another.

Pretend middle-class males, living in California, with gray hair, and a history of visiting Apple stores are good prospects for OtterBox.

It’s not that being a middle-class male, living in California, with gray hair, and a history of visiting Apple stores directly ties to interest in OtterBox. Rather, it just so happens that when consumers with said characteristics look at marketing content, in a certain sequence, and at a certain frequency, they’re more likely to make a purchase from OtterBox.

So, when a consumer uses Google Chrome to visit OtterBox.com, OtterBox drops a cookie to create a directly identifiable ID of the visitor.

The ID is reviewed amidst the larger set of people visiting the company’s digital properties. This includes pools of current and prospective customers. OtterBox’s marketers want to find audiences within these pools that resemble their existing customers.

In other words, OtterBox’s marketers are going to look at the “letters” inside the “envelope.” They are going to use cross-device graphs or lookalike modeling to ascertain the likelihood of someone becoming a customer.

Addressable marketing isn’t going away.

No one is threatening the ability of walled gardens and internet gatekeepers to offer addressable marketing.

The largest publishers will retain the ability to offer addressable advertising.

But will the gardens and gatekeepers allow marketers to advertise across multiple publishers?

Moreover, will they allow them to do so with the speed and competitiveness of today?

That remains to be seen, which is why the debate over addressability is NOT one of privacy. It is a debate over the future of the internet.

It doesn’t matter if the cookie lives or dies, walled gardens and internet gatekeepers will continue collecting consumer’s digital activity. Moreover, they’re going to associate digital activity with the consumer’s identity—something most marketers don’t currently do.

The walled gardens attempting to position themselves as the guardians of consumer privacy are unintentionally obscuring the truth. Walled gardens will continue to collect consumers’ personally identifiable information. They will also keep offering that information to marketers looking for real-time addressable advertising. The only thing that will change is the number of rivals the walled gardens are forced to compete with.

Put another way, the loss of cross-publisher IDs allows walled gardens to wipe out thousands of competitors in one fell swoop.

The future isn’t set in stone. Many individuals and organizations are working hard to preserve the existence of an Open Web that isn’t dominated by a few walled gardens. To learn more about Zeta’s position on addressability and its impact on the future of the digital space talk to us today!

- Engaging an audience.

- Measuring what happens following engagement.

- Improving the engagement process using the results of the measurement.

To power all three of these critical functions, marketers require a consistent cross-site identifier.

Think of the identifier as the address on the outside of an envelope:

Just as the address enables the mailman to deliver an envelope to the right house, the identifier allows marketers to deliver content to a given browser (or any other web-enabled application).

Thus this identifier (or “ID”) helps the marketer deliver their message to the right audience.

- With email, the identifier/ID is an email address.

- In a browser environment, the identifier/ID is stored in a cookie.

- In a mobile app, the identifier/ID is a mobile advertising ID (MAID).

Identifiers differ not just in which application or device they’re associated with. They also differ in whether they’re directly associated with a person (a.k.a, personally identifiable information) or a web-enabled device (a.k.a., pseudonymous identifiers).

The main distinction between these two is whether there’s a way to keep a real-world identity hidden from the organization using the identifier.

Marketers use pseudonymous identifiers for most advertising, so they don’t know the real-life identity of their audience.

This is a critical distinction:

Pseudonymous IDs do not equate to known identities.

A marketer using a pseudonymous ID might know that a nameless, faceless consumer is visiting ESPN.com. But they don’t know this consumer is named John Q. Smith, aged 47 years, living at 789 Main Street. Returning to the previous analogy, the identifier is the label on the envelope. It is how a marketer’s message (e.g., “Buy this product!”) reaches a given consumer. It is not the why.

The why is explained by the “letter” inside the envelope. The letter contains the consumer’s demographics, interests, buying history, search history, and more.

This inside-the-envelope information is what powers segmentation and audience construction. It explains why a marketer wants to engage one consumer more than another.

A hypothetical example

Pretend middle-class males, living in California, with gray hair, and a history of visiting Apple stores are good prospects for OtterBox.

It’s not that being a middle-class male, living in California, with gray hair, and a history of visiting Apple stores directly ties to interest in OtterBox. Rather, it just so happens that when consumers with said characteristics look at marketing content, in a certain sequence, and at a certain frequency, they’re more likely to make a purchase from OtterBox.

So, when a consumer uses Google Chrome to visit OtterBox.com, OtterBox drops a cookie to create a directly identifiable ID of the visitor.

The ID is reviewed amidst the larger set of people visiting the company’s digital properties. This includes pools of current and prospective customers. OtterBox’s marketers want to find audiences within these pools that resemble their existing customers.

In other words, OtterBox’s marketers are going to look at the “letters” inside the “envelope.” They are going to use cross-device graphs or lookalike modeling to ascertain the likelihood of someone becoming a customer.

Addressability is here to stay

Addressable marketing isn’t going away.

No one is threatening the ability of walled gardens and internet gatekeepers to offer addressable marketing.

The largest publishers will retain the ability to offer addressable advertising.

But will the gardens and gatekeepers allow marketers to advertise across multiple publishers?

Moreover, will they allow them to do so with the speed and competitiveness of today?

That remains to be seen, which is why the debate over addressability is NOT one of privacy. It is a debate over the future of the internet.

Consumer privacy isn’t the issue

It doesn’t matter if the cookie lives or dies, walled gardens and internet gatekeepers will continue collecting consumer’s digital activity. Moreover, they’re going to associate digital activity with the consumer’s identity—something most marketers don’t currently do.

The walled gardens attempting to position themselves as the guardians of consumer privacy are unintentionally obscuring the truth. Walled gardens will continue to collect consumers’ personally identifiable information. They will also keep offering that information to marketers looking for real-time addressable advertising. The only thing that will change is the number of rivals the walled gardens are forced to compete with.

Put another way, the loss of cross-publisher IDs allows walled gardens to wipe out thousands of competitors in one fell swoop.

What happens next?

The future isn’t set in stone. Many individuals and organizations are working hard to preserve the existence of an Open Web that isn’t dominated by a few walled gardens. To learn more about Zeta’s position on addressability and its impact on the future of the digital space talk to us today!